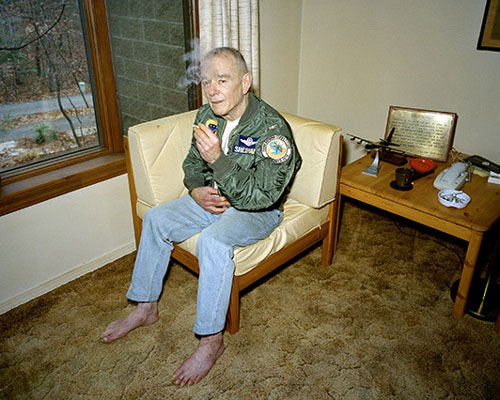

Dave Cline

August 1967-January 1968

“I remember before we went to Bo Tuc they had us set up for about a week in an area near the Cambodia border. We set up a battalion-size perimeter and we put out barbed wire and rigged up the whole perimeter with Claymore mines. They never attacked us there because they saw us setting all this up. They waited until the next night when we went to Bo Tuc and that night at two in the morning we got overrun by North Vietnamese.

All of a sudden mortar rounds started coming in. I was in a foxhole with two other guys, black guys, one named Jameson and the other named Walker. We’d sleep three in a hole. We were supposed to be a reserve support position, not a line position, and being in a reserve position we were able to all three of us sleep. So the mortar attack woke us up and all of a sudden we could hear someone about 30 meters in front of us yelling orders in Vietnamese. They were attacking the position next to us. They overran that position and one of them started running toward our hole. It was two in the morning so you couldn’t tell if he was an American or Vietnamese.

I was sitting cross-legged with my rifle pointed up at the entrance to the hole. We always put a sand bag cover on our foxholes so if we got mortared we’d have some protection from the shrapnel. All of a sudden this guy came up behind my hole and he stuck in his rifle. I saw the front side of an AK-47 and then a muzzle flash and I pulled my trigger. The bullet hit me in the knee and I blacked out from the impact. When I came to a few minutes later my weapon was jammed and my knee was shattered. Walker-who we used to call ‘Thump’ because he had the M-79 grenade launcher and that’s the sound it made-started shooting and Jameson pulled me out of the hole and lifted me on his back. We pulled back to the platoon CP which was a hole even further back and they stuck me in the foxhole with a bottle of Darvans and I lay there eating them Darvans all night to kill the pain.

That night the NVA overran a lot of our positions. We had flown in artillery and they overran the artillery, set the artillery rounds on fire. So they were blowing up and they’d cook off-a dull thud-type of explosion. It was the only night in Vietnam I thought I was dead for sure because the Vietnamese were all over the place charging and at night you couldn’t tell who was who. The fight went on all night. They were not able to kill us all and take over our positions so they withdrew before the sun came up. We took a lot of casualties. I’m sure they took a lot of casualties too.

In the morning they took me out of the foxhole and put me on a stretcher to medevac me out. They carried me over to my position and the guy who had shot me was dead. He was sitting up against a tree stump and he had his AK-47 across his lap and a couple of bullet holes up his chest. The sergeant started patting me on the shoulder. ‘Here’s this gook you killed. You did a good job.’

They used to have a big thing; first off it was a racial thing: they weren’t people; they were ‘gooks’. How you get people to kill people, you dehumanize them-make them less than human. They also used to have a big thing in my unit about Individual Confirmed Kills. You know, a lot of times we’d get into a firefight and everyone would start shooting and then you’d find some bodies later and you weren’t sure who individually shot them-you all did. But if you had an Individual Confirmed Kill and the person you killed was carrying an automatic weapon-not a semi-automatic-you would get a three-day in-country pass.

Sounds bizarre when you think about it. Sounds like hunting, But when we were fighting the Vietnamese, they were putting a high priority on capturing AK’s. So this sergeant is telling me, ‘Here’s the gook you killed.’ I looked at this guy; he was about my age and I started thinking, ‘Why is he dead and I’m alive?’ It was pure luck that I had my rifle aimed at his chest while his was aimed at my knee-not anything to do with being a better soldier or fighting for a better cause.

Then I started thinking, ‘I wonder if he had a girlfriend? How will his mother find out her son is dead?’ What I didn’t realize at the time, but did later, was that I was refusing to give up on his humanity. And that’s what a lot of war is about: denying your enemy’s humanity. That’s where a lot of guys came back and still had a lot of hatred and anger. That was the point at which I felt I had to do more than go back home and try to pretend I wasn’t in the war zone. The senselessness of the whole thing was right in front of me. And if you asked me about what I thought about at that moment I would have said, ‘Old men send young men to wars, so why doesn’t Lyndon Johnson and Ho Chi Minh fight it out and let us all go home.'”